Living Through Fear, or Living Through Rap?

November 18, 2019

Damnation — condemnation or eternal punishment in hell. Through time mankind has played with the idea of an afterlife and how one ends up there. Whether you spend eternity in bliss or sorrow is chosen by the gods that you do, or do not, believe in. Many philosophers and religious critics argue that religion is just one way that we are controlled by people in charge. The fear associated with suffering forever can keep people falling in line and submitting. This method of causing panic and fear is often used by governments and in our personal relationships every day by parents, partners, and even ourselves.

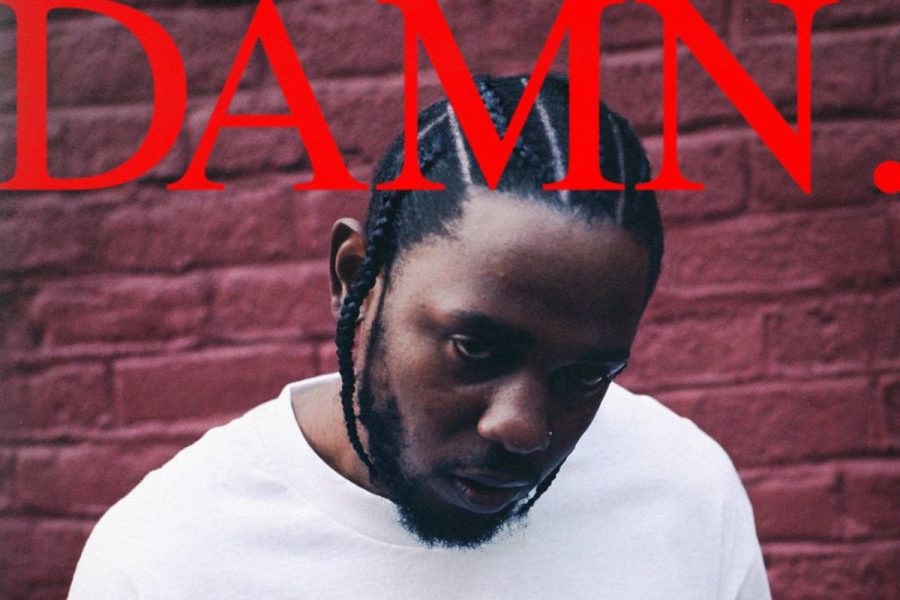

Kendrick Lamar talks about this same abuse in his 4th studio album on the track Fear. Through the LP Lamar deconstructs his relationships with large concepts that are vital to the human experience; pride, lust, fear, love and God are some of the topics covered in the Pulitzer Prize winning body of work.

Each of the records on the project ask the listener to look inside and reconsider their connection to the topic, however the track Fear does this the best. He opens the song with a voicemail from his cousin Carl Duckworth. In the message, Duckworth says that part of the reason that Lamar feels rejected by God is because he is part of a lost and cursed tribe of Israel; when the rapper starts following God’s commandments the curses of sadness, paranoia, and depression will subsist.

This sets the tone for the first verse of the song in which Lamar hints at the ways that he’s been raised into this life of fear and avoiding risk. He swiftly makes connections between the ways that a parent hurts on their children out of fear that they might be harmed elsewhere. Author Ta-Nehisi Coates talks about this same experience in his novel Between the World and Me when he laments: “violence rose from the fear like smoke from a fire, and I cannot say whether that violence, even administered in fear and love, sounded the alarm or choked us at the exit.” (16-17) The physical punishment that Lamar talks about is common in the Black community. Growing up, my friends and I would sit and joke about the ways that we were punished by our parents. We would talk about whose momma was crazier and who got hit with the most outlandish item. Was it a switch off a tree? A belt? Plastic spoon? Although the general American public would argue that we turned out fine I cannot say the same for others in my community. Unfortunately, this same hostility can act as a sort of beginning for the behaviors that make an adolescent engage in things that the parent is trying to stop such as bullying, fighting, intimidation and drug use. This idea is shown in the following verse where Lamar raps, “If I could smoke fear away I’d roll that ‘mothafucka’ up and then I’d take two puffs.” (Lamar)

After the first chorus Lamer talks about his intense desire to confront fear in his life, he then spills upon the listener the anxieties that he had as a 17 year-old in Compton and the many ways that death was an omnipresent concern. Interestingly, it seems that his largest fear was death and not any of the other things that an adolescent could be worried about at his age. Survival is a delicate process of trying to navigate the violence and everyday dangers and death could happen from something as simple as, “walkin’ back home from the candy house,” or, “tryna’ defuse two homies arguing.” (Lamar) This verse firmly shows that for the youth of Compton an early death is not a distant fear. It is drilled into you from a young age that violence, physical pain and suffering are the results of doing the wrong thing. This delicate situation is not limited to the youth of Compton. It is predictable and found in many urban cities around the United States.

“To be black in the Baltimore of my youth was to be naked before the elements of the world, before all the guns, fists, knives, crack, rape, and disease. The nakedness is not an error, not pathology. The nakedness is the correct and intended result of policy, the predictable upshot of people forced for centuries to live under fear.” (Coats 17)

For the young Lamar the pressures are too much. He ends the verse illustrating his desire to be able to control his environment and be free in the same ways that many Black youths in America long to be.

Again, Lamar return to the same bridge following this verse but now it has a different feeling. This time, Lamar is trying to escape the challenges of life in Compton. A life filled with gang violence, poverty, and drugs. Smoking in this case is not a way for him to rebel or escape the fear he feels at home; it’s a way for him to deal with the systemic oppression and dangers of growing up in a world that was not created for him to succeed. “When you are a black man growing up in the streets of Compton, such uncertainty can feel constant, no matter what path one chooses to take. So what exactly is the point of righteousness again?” (Reynolds)

In the third verse we find our third and final time skip to the near present. Lamar opens this verse by saying that during his life he has become used to being afraid. It’s a constant motivator and driving force. However, for him, this fear is still makes him uncomfortable. He talks of fear of losing creativity and his love, his reputation — his pride. This is different from his other music. In songs like “I” and “Alright” from his celebrated album “To Pimp a Butterfly” in which Lamar paints himself as a self-assured artist ready to take on the world fearlessly.

“In the wake of unrest in Ferguson and two years after the Trayvon Martin verdict, racial tensions in the US were the highest they’d been since the Civil Rights Era. Young black people were looking for someone to look to in a time of crisis. Knowing that, Kendrick seemed to feel obligated to dedicate himself to the cause by addressing the social climate in his music.” (Burney)

However, this is not that Kendrick Lamar. This is the rapper at his most vulnerable. In this verse he speaks directly to the audience and tells us that he is afraid. He fears that his words will fall on deaf ears or be confused for something that it is not. He fears that he’ll die alone. As a listener it’s a moment that reminds you that Lamar is human; it serves as an important moment that tells us that even though he is a celebrated writer, artist, and musician he too feels sorrow and regret.

“How they look at me reflect on myself, my family, my city

What they say ’bout me reveal if my reputation would miss me

What they see from me would trickle down generations in time

What they hear from me would make ’em highlight my simplest lines” (Lamar)

Here Lamar is directly talking about a moment in which Fox News commentator Geralto Rivera said in reference to Lamar’s 2015 BET Awards performance that, “Hip-Hop has done more damage to young African-Americans than racism.” (Rivera) This isn’t the first time that he’s had to deal with critics who disagree with his messages that tell Black youth that their stories aren’t happening in isolation and that there is meaning in their suffering. However, this moment was especially hard hitting because it places his art at the front of the problem. Lamar also samples audio of Rivera on the first track of the album “Blood”. His use of this audio is very interesting because it goes back to the Hip-Hop tradition of being sharp and directly challenging your opponents but it also shows that Kendrick is very aware of the potential for his messages to be weaponized. “Kendrick is presented as the only rightful voice in our struggle, his words are picked through with a fine tooth comb. There’s no room for half-assed apologies and excuses.” (Burney)

Also, we see the rapper again talk about the biblical references mentioned earlier in the beginning of the track with the bar, “Cause’ my DNA won’t let me involve with the light of God,” referencing the curses of the Israelites in the song’s opening. He also goes on to say, “All this money, is God playin’ a joke on me? Is it for the moment and will he see me as Job? Take it from me and leave me worse than I was before?” (Lamar) This bar is referring to the biblical story of Job who was one of God’s most loyal servants. As a test of his loyalty God allowed him to be tortured and have his life ransacked by the devil. Lamar fears that his torment of fear may be divinely caused. It’s common within Black communities to assume that some suffering may come from Heaven or be caused by God. As if you’re being tested to make you stronger and better. Often during church services, a pastor will say something along the lines of, “weeping may endure for the night, but joy comes in the morning.” There’s almost a tendency to feel that suffering is justified and valiant and Lamar seems to be using the same type of reasoning. Lamar appears to be struggling and blaming himself for the things that he is facing in his life.

The third verse directly flows into the 4th verse skipping the smoking hook that we’ve seen repeated throughout the track. The listener can assume that this is because this is no longer a young Lamar speaking to the audience. This version of the artist is older and wiser. He no longer wishes to smoke his problems away. He’s looking for peace. He wants to confront these feelings because he knows at the end of the song that once death comes, the chance for closure is gone. He makes one final list of things that he fears. Almost like to making a to do list. He presents them for the listen like he’s crossing them off; speaking them into the mic for one last time. The entire 4th verse has an eerie feeling of finality.

“Fear, what happens on Earth stays on Earth

And I can’t take these feelings with me, so hopefully they disperse

Within fourteen tracks, carried out over wax

Searchin’ for resolutions until somebody get back”(Lamar)

In this last line he is talking about the second coming of Christ that is foretold in The Bible. At this point in the song it becomes clear that for Lamar living through fear is not how he wants to continue his life. He would rather spend his time searching for answers without success than being fearful like his has been in his past. He’s sure of himself but still lacking hope. He even goes so far as to end the song with a sad couple of bars: “Goddamn you. Goddamn me. Goddamn us. Goddamn we. Goddamn us all.” (Lamar)

Through this track we’re called to look at the way that fear has found itself in the lives of poor urban African Americans and specifically we’re given a view into the experiences and worries that has shaped Kendrick Lamar into the artist that he is today. Lamar’s experiences as a poor young man from Compton mirror the plight of many Black Americans in this country and many religious individuals around the world. The insecurities and hopelessness depicted in this song may be abstract for some but are the reality for many people who are not given the luxury of having safety and security at home or in the world. Lamar was able to find his escape mentally and physically through the music that he listened to and made; he begs us to question if we, like him, are, “living through fear, or living through rap.”

Works Cited:

Kendrick Lamar. “Fear.” DAMN., Daniel Alan Maman.

Coates, Ta-Nehisi. Between the World and Me. First edition. New York: Spiegel & Grau, 2015.

Reynolds, Sam, and Sam Reynolds. “Perspective and Context: The Densely Packed Psychology of Kendrick Lamar’s ‘DAMN.”.” Medium.com, Medium, 2 May 2017, medium.com/@renwald12/perspective-and-context-the-densely-packed-psychology-of-kendrick-lamars-damn-89d92b010934.

Burney, Lawrence. “Why Kendrick Lamar’s ‘FEAR’ Feels so Perfect.” Noisey, VICE, 18 Apr. 2017, noisey.vice.com/en_us/article/9a4a35/why-kendrick-lamars-fear-feels-so-perfect.

Rivera, Geralto. Fox News. 2015. Newscast